Ferrari as a dare, not a dream

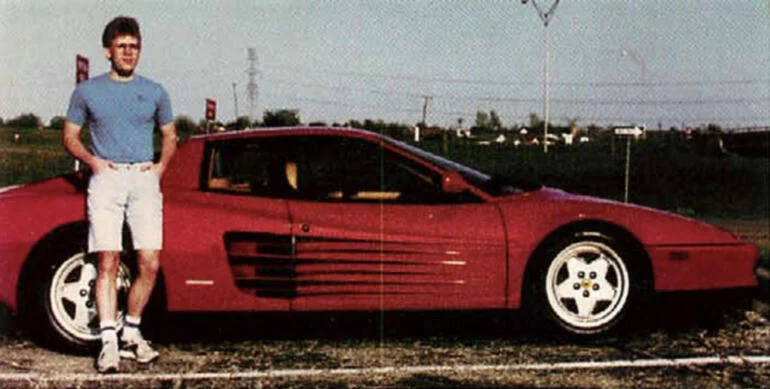

The story opens not in Maranello, but in Dallas, Texas, with a casually dressed John Carmack wandering into a dealership and spotting a slightly forgotten 1987 Ferrari 328 GTS sitting in the back. According to Carmack himself, the car cost roughly $300,000 at the time, a serious sum but hardly sacred to a man already thinking in terms of frame rates and optimization. The salesman’s advice was pure Ferrari theater: if someone revs next to you, just act like you have a thousand horsepower. Carmack reportedly found that idea offensive, almost lazy, because to him speed was not an illusion but a measurable truth. Why look fast when you could actually be fast?

That single moment explains everything that followed, because Carmack never bought machines to admire them. He bought them to interrogate them. Within months, the naturally aspirated V8 was handed over to Bob Norwood of Norwood Autocraft, one of the few specialists willing to violate Ferrari orthodoxy. The result was a turbocharged 328 pushing power from around 270 horsepower to nearly 500, an absurd figure for a car Ferrari intended to remain politely restrained. Worth noting is that Carmack did not even store it like a trophy; he famously joked online about parking multiple Ferraris outside a low-end apartment, which tells you exactly how little image mattered to him.

The 328 also became a cultural artifact in an entirely different world. In a move that still feels surreal decades later, Carmack offered the modified Ferrari as the grand prize for Red Annihilation, a Quake tournament that helped invent professional esports. Dennis “Thresh” Fong drove away with a Ferrari instead of a trophy cup, making it, reportedly, the first supercar ever awarded for competitive gaming. In one gesture, Carmack collapsed the distance between digital speed and mechanical speed. Ferrari was no longer a luxury symbol; it was loot.

When optimization turns into heresy

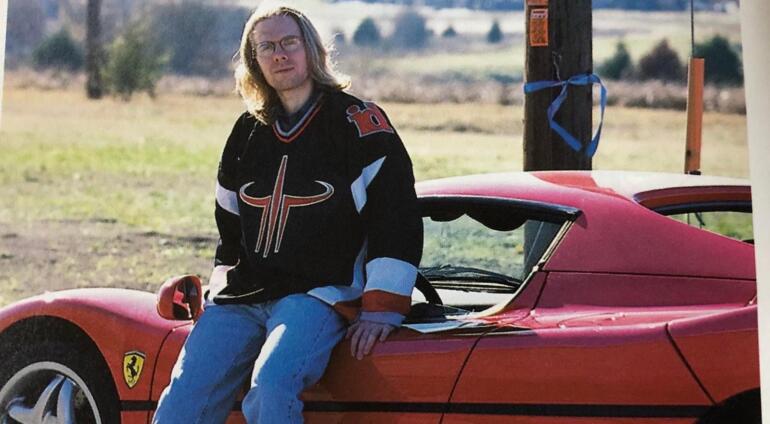

If the 328 was a proof of concept, the Ferrari Testarossa was full-scale experimental research. Introduced with its iconic side strakes and flat-12 engine, the car already carried an aura of excess, but Carmack saw untapped potential. Twin turbos were installed, along with nitrous, revised suspension geometry, and tires better suited to the violence he intended to unleash. According to dyno sheets Carmack has referenced over the years, the car produced around 1,009 horsepower at the rear wheels, a figure that still sounds unhinged today. His preferred metric was not 0–60 bragging rights, but the brutal 50–150 mph surge that separates theater from terror.

The Testarossa quickly became infamous around id Software’s offices. Carmack has written about late-night runs on nearby straightaways, loud enough that employees could identify his arrival by sound alone. The car broke constantly, snapping input shafts and living on jack stands more often than pavement, but that only made it more interesting. To Carmack, failure was not a flaw but feedback. Each breakage was data, and each fix was a patch.

Then there was the Ferrari F40, the one car even Carmack mostly respected as-is. Designed as a barely civilized race car, it demanded attention and punished complacency, and he limited his changes largely to boost-related tweaks. The restraint, however, was temporary. When Carmack attempted to buy the F50, Ferrari’s patience ran out. As he later explained publicly, the dealer would not even place him on the waiting list, effectively blacklisting him for his turbocharged heresies and implied criticism that Ferraris were not as fast as they looked. For Ferrari, this was sacrilege; for Carmack, it was simply confirmation that he had found the final boss.

Beating Ferrari and choosing silence

Being denied factory approval did not stop Carmack; it merely rerouted him. When a U.S.-leased F50 became available privately, he bought it anyway, completing what he later described as owning four Ferraris in total: the 328, the Testarossa, the F40, and the F50. And then, in the most predictable move imaginable, he sent the F50 straight to Norwood Autocraft for twin turbos. Depending on whose numbers you believe, the car made roughly 602 horsepower at the rear wheels or close to 900 metric horsepower overall, figures Ferrari never intended to see. Carmack would later joke that he had effectively beaten Ferrari four times, a line delivered with programmer’s deadpan confidence.

There were side quests, too, the kind that fascinate collectors and engineers alike. One involved a carbon-bodied 288 GTO project fitted with a billet 5.0-liter V12, twin turbos, dual fuel systems, and a surreal arrangement of 24 injectors around the intake. Photos circulated, the project stalled, and the car lingered unfinished, like abandoned source code waiting for a future commit. It was the purest expression of Carmack’s mindset: curiosity over completion.

And then, without drama, he walked away. As Carmack has said on X, he gave up the turbo Ferrari habit, moved to electric, and bought Tesla Roadster number 30 before settling into a Tesla Model S P100D. He famously called it the best car he had ever owned by far, a statement that lands like a mic drop given the machinery that came before it. There is something deeply poetic in that ending. Ferrari was not defeated with noise or spectacle; it was simply out-optimized, patched over, and left behind by a man who never wanted a dream car, only the fastest possible solution.